The Work of Edmonia Lewis:

Much of Lewis’ work was based on literary, religious, racial, or classical images, and was known for its expression of ethnic dignity. She sculpted figurative images that spoke to her dual ancestry and were based on scenes from the epic Longfellow poem The Song of Hiawatha and the experiences of people of color following the abolition of slavery. Other figures reflected her Catholic faith or classical imagery. While Lewis used some features of dress and adornment to express a subject’s culture, the facial features in her figurative work retained the appearance of any white, Neoclassical male or female. Her work is described as presenting issues of social justice in a subtle and nuanced way.

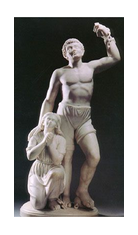

Forever Free, 1866

Forever Free is one of Lewis’ most well known sculptures. It depicts a Black man and woman emerging from the bonds of slavery, the shackles broken.

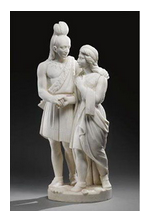

The Marriage of Hiawatha and Minnehaha, 1868

Lewis did at least three other figure groups based on the Hiawatha poem. Longfellow sat for a portrait bust in Lewis’ studio when he visited Rome in 1869.

This a another of the figure groups based on Longfellow’s poem. Hiawatha has just presented the arrow maker a deer as a token of marriage to his daughter who is weaving rushes.

Hagar, 1875

The story of Hagar is from the Old Testament. Abraham’s wife Sarah banishes her young Egyptian maidservant to the wilderness in a jealous rage. Hagar despondently looks toward heaven as she searches for water in the desert.

Poor Cupid or Love Ensnared, 1876

This is one of Lewis’ mythical scenes which depicts Cupid with his hand caught in a trap as he reaches for a rose. (see photo in Part I)

The Death of Cleopatra, 1876

Cleopatra chooses to die by letting a poisonous asp bite her rather than be imprisoned by Octavia who had just defeated her armies and later became Augustus Caesar, the first Imperial leader of Rome.

Many consider this Lewis’ masterpiece. The 3000 pound sculpture was prepared for the Centennial celebration of America’s Declaration of Independence and was shipped to Philadelphia for the occasion. Lewis was one of two black artists invited to participate in the event. The sculpture was deemed the most important sculpture in the American section at the Exposition and was given a place of honor in the desirable rotunda area. Although Cleopatra was Egyptian and black, Lewis did not give her Africanized features. It is speculated she wanted to keep some distance from her subject as a black Queen and herself as a black female. Lewis is known to have said she wanted to be known for her art rather than for her heritage.

This sculpture has an interesting history. It didn’t sell at the exhibition so it was placed in storage as Lewis could not afford to ship it back to Italy. It was brought to an exhibition in Chicago in 1878 and seems to have sold there and been placed in a saloon. A gambler bought it from the bar owner to place on the grave of his racehorse named Cleopatra. In the 1970s it was eventually moved to a construction storage yard elsewhere in Chicago where it remained for years unprotected from the elements. A dentist finally acquired the sculpture and placed it in storage in the Forest Park Mall. Attempts to improve its damaged condition included painting it. The dentist eventually contacted the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a specialist on Edmonia Lewis was notified. At last the sculpture was finally recognized, properly restored and donated to the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in 1994.

Final Years

There is little information on the last decade of Edmonia Lewis’ life. Around the 1880’s, demand for work in the Neoclassical style had diminished. She continued to exhibit her work until the 1890’s, and was visited during this period by Frederick Douglas when he toured Rome. There is indication that by 1901 she had moved to London. There she died in 1907 of Bright’s disease according to her death certificate.

What is certain is that she defied adversity and overcame many challenges to follow her calling as an artist. Despite her own experiences of racism and sexism and the gender and racial norms of the 19th century, Lewis found a place and a means of expressing through her art stories of women, Indigenous figures and people of color with reverence and beauty.

Current Interest

The rescue and restoration of the dying Cleopatra revived interest in Edmonia Lewis’ life and career. Her work can be seen in the permanent collections at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. as well as museums in Detroit, Baltimore and New York City. Her works also are in various churches in the U.S. and Europe. Other of her sculptures, missing for decades, continue to be discovered today.

Leave A Comment